Distributed Lock Failure: How Long GC Pauses Break Concurrency

When Your Distributed Lock Lies to You

Your service just corrupted data in production. Two processes both withdrew money from the same account at the exact same moment, even though you implemented a distributed lock. How did this happen?

The Problem Nobody Talks About

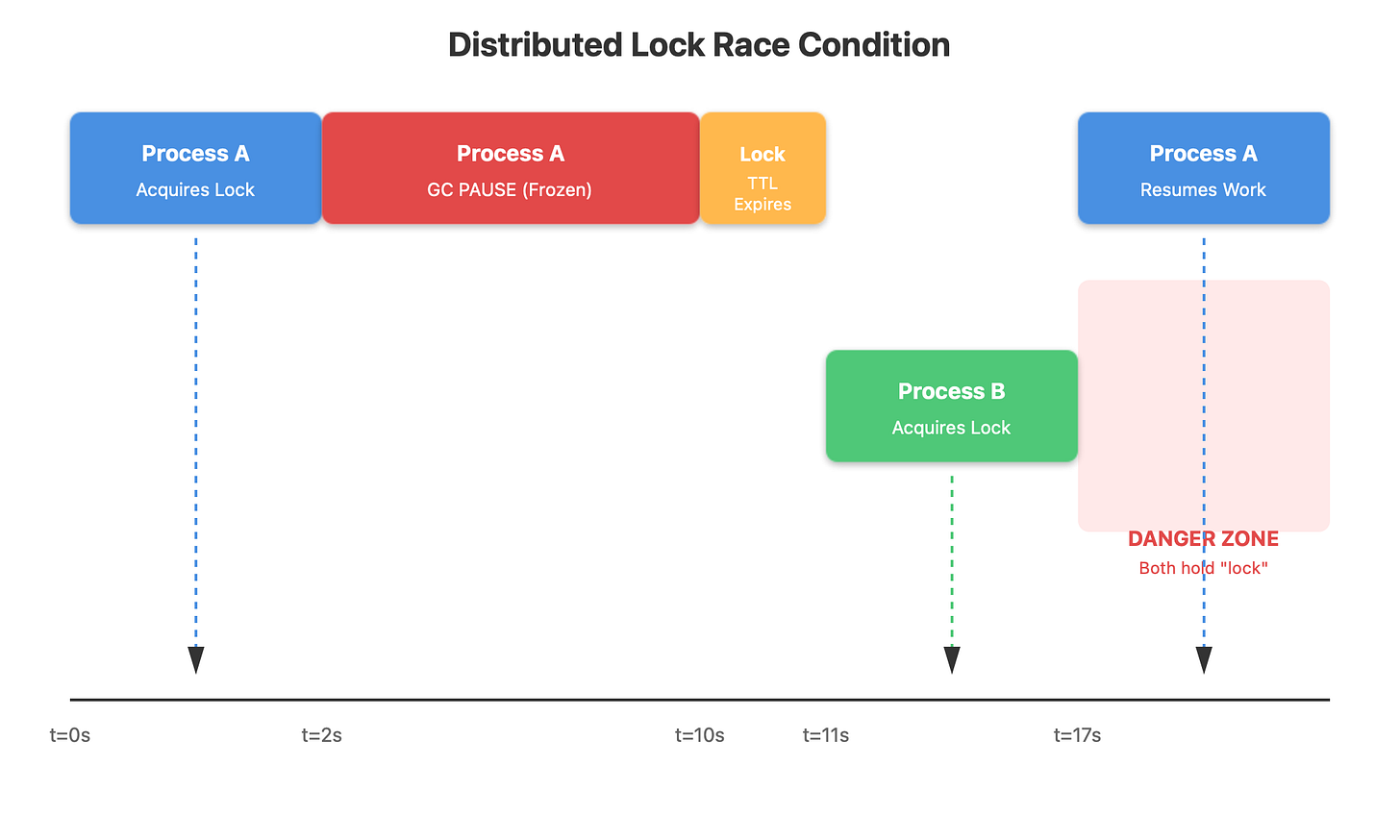

Here’s what happened: Process A grabbed the lock from Redis, started processing a withdrawal, then Java decided it needed to run garbage collection. The entire process froze for 15 seconds while GC ran. Your lock had a 10-second TTL, so Redis expired it. Process B immediately grabbed the now-available lock and started its own withdrawal. Then Process A woke up from its GC-induced coma, completely unaware it lost the lock, and finished processing the withdrawal. Both processes just withdrew money from the same account.

This isn’t a theoretical edge case. In production systems running on large heaps (32GB+), stop-the-world GC pauses of 10-30 seconds happen regularly. Your process doesn’t crash, it doesn’t log an error, it just freezes. Network connections stay alive. When it wakes up, it continues exactly where it left off, blissfully unaware that the world moved on without it.

Why Time-Based Locks Are Fundamentally Unsafe

The root issue is that we’re using time to solve a problem that isn’t really about time. When you set a TTL on a lock, you’re making a bet: “I’ll finish my work before this timer expires.” But distributed systems don’t let you make promises about time. GC pauses, network delays, CPU throttling in containers, process scheduling delays, or even accidentally sending SIGSTOP to your process - any of these can make your process miss its deadline.

Most articles tell you to “tune your TTL” or “optimize your GC settings.” That’s like treating a broken leg with aspirin. You’re addressing symptoms, not the disease. Even with perfectly tuned GC, you can’t eliminate pauses entirely. G1GC and ZGC have reduced pause times dramatically, but at 128GB+ heap sizes, you still see occasional long pauses. And that’s just GC - you also have kernel scheduling, container CPU throttling, and network partitions to worry about.

The real kicker is that monitoring won’t save you. You might track lock hold times and never see a problem, because the GC-paused process isn’t running to report metrics. The monitoring system gives you false confidence right up until data corruption happens.

The Solution: Fencing Tokens

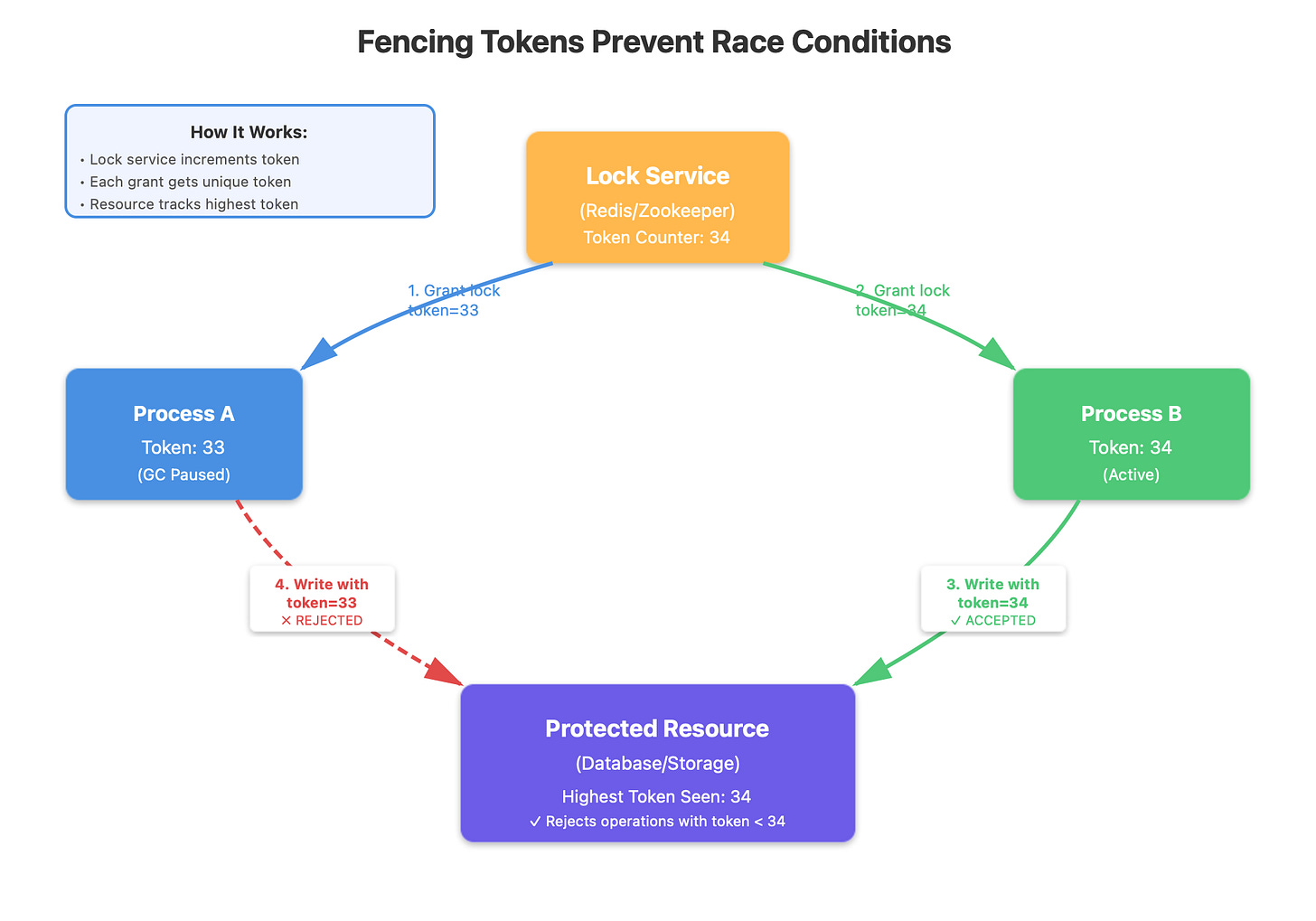

Here’s what companies that handle billions of transactions actually do: they use fencing tokens. Every time the lock service grants a lock, it includes a monotonically increasing number with it. The critical resource being protected only accepts operations from the highest fencing token it has ever seen.

Process A grabs lock with token 33, gets GC paused. Lock expires. Process B grabs lock with token 34 and successfully writes to the resource. Process A wakes up, tries to write with token 33, and the resource rejects it because it already saw token 34. The race condition is prevented at the resource level, not the lock level.

This is the insight that most engineers miss: the lock service can’t solve this problem alone. The resource being protected must participate in the protocol. Zookeeper provides this with its “zxid” transaction ID. Consul and etcd have similar mechanisms. Redis doesn’t provide fencing tokens out of the box, which is why using Redis SETNX alone for distributed locking is considered unsafe by distributed systems experts.

Real-World Examples

At a major payment processor I worked with, they discovered they’d been double-charging customers about once every 10,000 transactions due to this exact issue. Two worker processes would both believe they held the lock on an account. The financial impact was significant, but worse was the reputational damage when customers noticed.

E-commerce platforms face this with inventory management. Two checkout processes both decrement the last item in stock. Both succeed. You’ve now oversold by one unit. Multiply this across thousands of products and millions of transactions, and you’re hemorrhaging money in customer service costs and rushed shipping fees to fix the mistakes.

Leader election systems are particularly vulnerable. If two nodes both believe they’re the leader, they’ll both write to the database with conflicting decisions. This is why mature systems like Kubernetes use etcd (built on Raft consensus) rather than simple distributed locks. Raft solves the fencing problem through its term numbers and log indexes.

What You Should Actually Do

First, question whether you need a distributed lock at all. Most use cases are better served by optimistic locking at the database level with version numbers or timestamps. Postgres advisory locks combined with proper transaction isolation often work better than distributed locks because the database itself enforces consistency.

If you genuinely need distributed coordination, use a proper consensus system like etcd, Consul, or Zookeeper. These systems were designed from the ground up to handle failure modes like GC pauses. They provide fencing tokens natively and have been battle-tested at massive scale.

When you implement your protected resource, always accept and validate fencing tokens. Keep track of the highest token you’ve seen and reject any operations with lower tokens. This simple check prevents the entire class of problems we’ve discussed. The lock can fail, the network can partition, GC can pause for minutes - none of it matters because the resource itself is the final authority on what operations it accepts.

For systems that absolutely must use Redis (maybe you’re already running it and can’t add another service), implement your own fencing token mechanism. Use Redis’s INCR command to generate monotonically increasing tokens, and include them with every lock grant. Then enforce token validation at the resource level. It’s more work, but it’s the difference between a reliable system and a ticking time bomb.

The hard truth is that distributed systems are fundamentally about handling uncertainty. Time-based mechanisms like TTLs give us a convenient fiction that we can reason about ordering and exclusivity. But when you’re protecting critical resources - money, inventory, data consistency - you need mechanisms that work even when time becomes unreliable. Fencing tokens give you that guarantee.