UDP vs. TCP in Multiplayer Gaming: State Synchronization and Lag Compensation

Why TCP Kills Multiplayer Gaming

In high-stakes online gaming, “lag” is rarely just about raw connection speed. It is usually a complaint about how the network protocol handles data loss. The choice between TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) and UDP (User Datagram Protocol) determines whether a game feels responsive or broken.

While TCP is the backbone of the reliable web, its core mechanisms make it fundamentally unsuitable for real-time physics simulations.

Head-of-Line Blocking

TCP prioritizes order and reliability. It guarantees that every byte sent is received in the exact sequence it left the sender. While this is essential for loading a webpage (you don’t want HTML tags arriving out of order), it is catastrophic for a 60 FPS shooter.

The specific failure point is Head-of-Line (HOL) Blocking.

Imagine a stream of packets representing player positions: #47, #48, #49, #50.

Packet #47 is dropped due to network congestion.

Packets #48-50 arrive successfully at the client.

TCP halts processing: It buffers

#48-50and refuses to release them to the game engine until#47is retransmitted and received.

The Consequence:

The Freeze: The game state freezes for the duration of the Round Trip Time (RTT)—often 100ms or more.

The Warp: Once the missing packet arrives, TCP flushes the buffer. The game engine processes 100ms of movement in a single frame, causing the player to teleport or “rubber-band.”

At 60 FPS, the game expects a frame every $16.6ms$. A 100ms delay freezes the game logic for 6+ frames. In a competitive environment, this renders the game unplayable.

The Solution: UDP “Fire and Forget”

UDP is connectionless and offers no guarantees. It sends packets blindly.

No Retransmission: If Packet #47 is lost, the client never receives it.

No Blocking: Packet #48 is processed immediately upon arrival.

In real-time gaming, freshness matters more than completeness. Packet #47 contained the player’s position at $T=0$. Packet #48 contains the position at $T+16ms$. Since the player is no longer at $T=0$, the data in Packet #47 is obsolete. There is no value in pausing the game to retrieve history that has already been superseded.

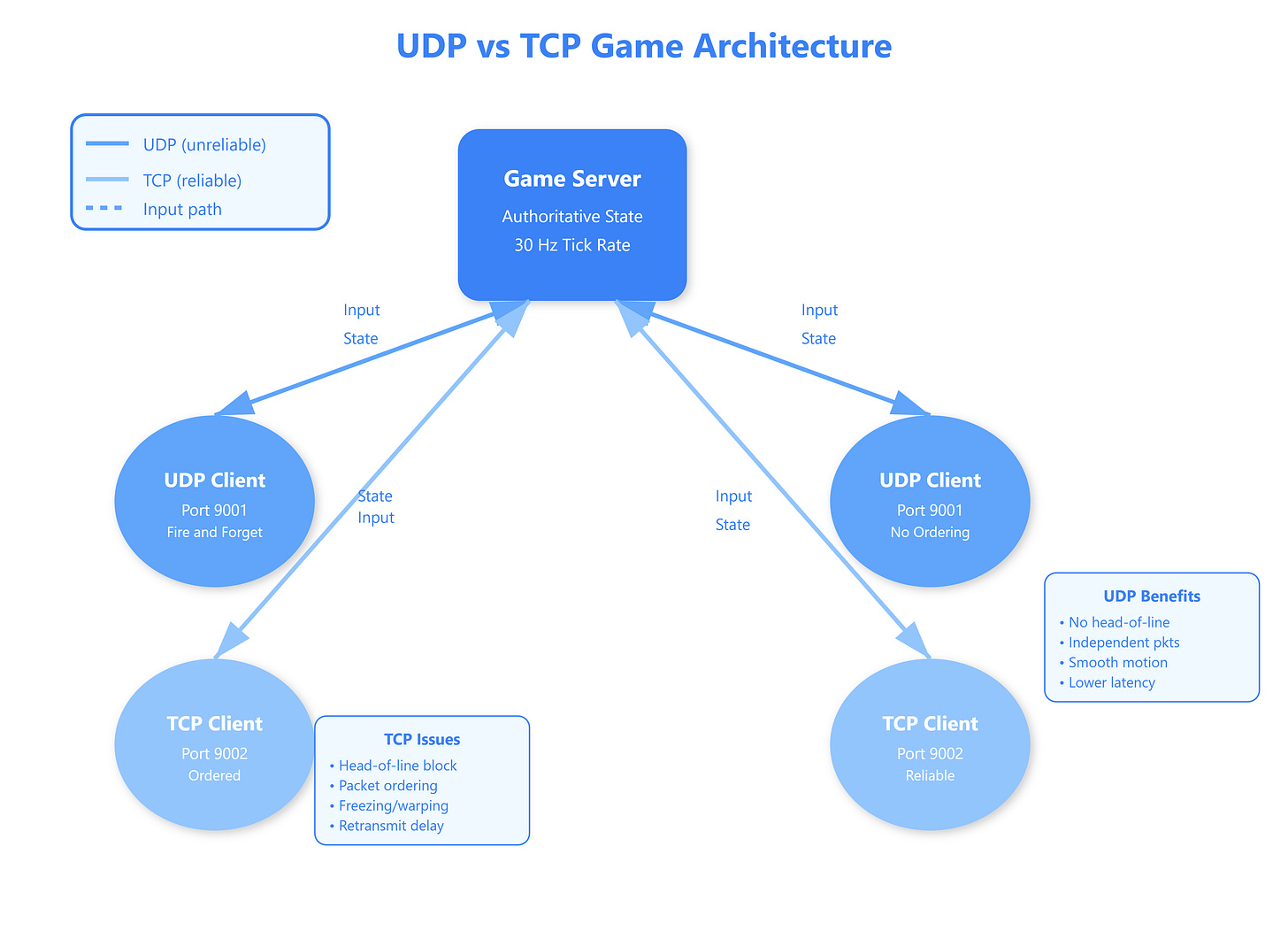

The Architecture of “Unreliable” Gaming

Because UDP provides no guarantees, game developers must build a custom reliability layer on top of it. This “Netcode” stack relies on three primary strategies to maintain the illusion of continuity.

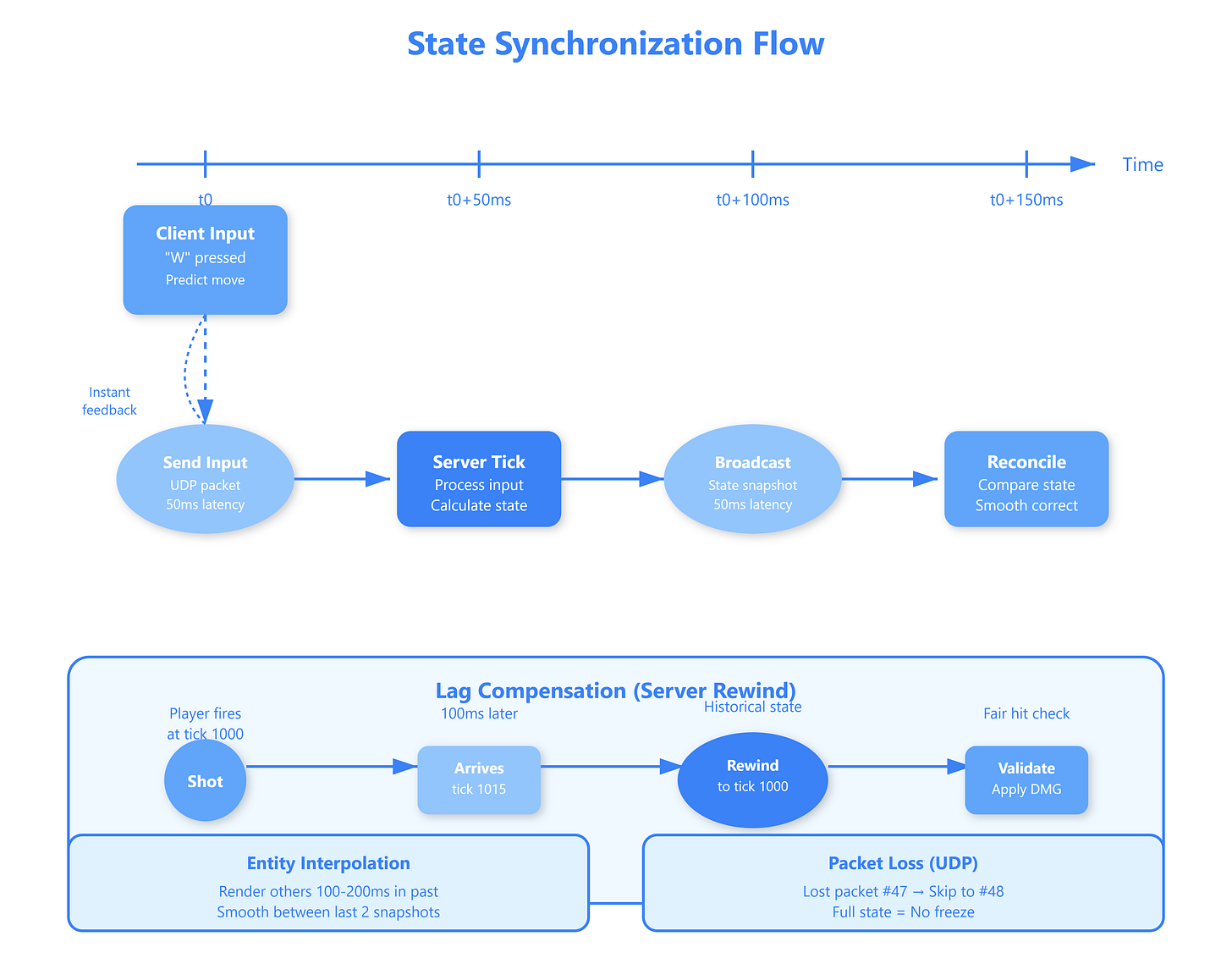

1. Client-Side Prediction (Zero Latency Feel)

If the client waited for the server to confirm every move, the game would feel sluggish. To solve this, the client predicts the outcome of inputs.

Process: When you press ‘W’, the local client immediately moves your character.

Feedback: The input is sent to the server.

Result: The game feels instantaneous, masking the 50-100ms round-trip time.

2. Server Reconciliation (The Source of Truth)

The server runs the authoritative simulation. It receives the input, calculates the actual position, and sends it back.

Comparison: The client compares its predicted position with the server’s actual position.

Correction: If they differ (e.g., the server calculated a collision the client missed), the client “reconciles” by snapping or blending the character to the server’s coordinates. This is what players see when they experience “rubber-banding”—it is the client correcting a prediction error.

3. Entity Interpolation (Smoothing Others)

You never see other players where they are; you see where they were.

Because UDP packets arrive at irregular intervals (jitter), rendering an opponent’s raw position would look jerky.

Buffer: The client holds a buffer of recent snapshots (e.g., $50ms$ worth of data).

Interpolation: The game renders the opponent by interpolating between the two most recent snapshots in the buffer.

Trade-off: This introduces a slight visual delay (you see the enemy ~50ms in the past) in exchange for smooth movement.

Critical Missing Pieces: Reliability & Bandwidth

The original explanation simplifies data transmission. Modern engines do not simply “spam full snapshots” blindly; they use sophisticated optimization techniques.

Delta Compression

Sending the full state of a massive world (positions, rotations, velocities, inventory) 60 times a second would destroy bandwidth.

Instead, engines use Delta Compression.

Baseline: The server knows the client has successfully received Snapshot #100.

Delta: For Snapshot #101, the server only sends the bits that changed relative to #100.

Result: Massive bandwidth savings. If a player stands still, the delta is near zero.

Selective Reliability (RUDP)

While movement data is expendable, other data is not. You cannot “fire and forget” a “Player Died” event or a “Match Ended” signal.

Games implement a mixed-mode protocol:

Channel 1 (Unreliable): Movement, physics, visual effects. (If lost, ignore).

Channel 2 (Reliable): Chat, damage events, item pickups. (If lost, resend).

This custom “Reliable UDP” (RUDP) layer implements TCP-like ACKs only for the specific packets that need them, avoiding global blocking.

Lag Compensation (Rewind Time)

Since you see enemies in the past (due to Interpolation), your crosshair is aiming at a “ghost.” If you fire, you will miss the real server-side player.

To fix this, servers use Lag Compensation:

Server receives your “Fire” packet timestamped at $T=1000$.

Server rewinds the positions of all enemies to where they were at $T=1000$.

Server calculates the hit.

Server restores the current state.

Summary for System Design

If you are designing a real-time multiplayer system, avoid TCP for the gameplay loop.

Transport: Use UDP to avoid Head-of-Line blocking.

Sync Strategy: Use Server Authoritative state with Client Prediction.

Optimization: Implement Delta Compression to reduce bandwidth.

Handling Jitter: Use a Jitter Buffer and Interpolation for smooth rendering of remote entities.

Real-World Implementations

GitHub Link

https://github.com/sysdr/sdir/tree/main/UDP_vs_TCP_in_Multiplayer_Gaming/game-protocol-demoValve’s Source Engine (Counter-Strike, Team Fortress 2) pioneered client-side prediction and lag compensation in the early 2000s. Their “rewind the world” technique became industry standard. They expose cl_interp settings, letting competitive players tune interpolation vs. prediction trade-offs—lower values reduce enemy movement delay but increase jitter on poor connections.

Riot’s Valorant uses a hybrid approach with aggressive lag compensation (up to 70ms rewind) and strict server-side validation to prevent cheating. They transparently display network performance with per-frame latency graphs, educating players about network vs. game performance issues. Their netcode synchronizes timestamped packets to sub-millisecond precision using NTP-synced clocks.

Rocket League faces unique challenges: physics simulation requires deterministic state synchronization. They use a fixed 120 Hz simulation with UDP state broadcasts and custom “physics rewind” for ball collision validation. Slight prediction errors in ball trajectory get smoothly corrected using Bezier interpolation over 3-4 frames, imperceptible to players but crucial for consistent gameplay.

Architectural Considerations

Implementing UDP game networking requires building observability into your transport layer from day one. Monitor per-client packet loss rates, latency histograms, and jitter (latency variance). Expose these metrics in-game so players can diagnose connection issues versus game bugs.

Cost implications: UDP reduces server bandwidth by 15-30% compared to TCP because there’s no ACK overhead and no retransmission of superseded state. At scale with millions of concurrent players, this translates to measurable infrastructure savings.

When to avoid UDP: Turn-based games, lobby systems, matchmaking, and chat absolutely should use TCP or WebSocket (TCP-based). Only the real-time gameplay loop demands UDP’s characteristics. Overusing UDP increases complexity without benefit.

Integration with game engines: Most modern engines (Unity, Unreal) provide high-level networking libraries that abstract UDP complexities. However, understanding the underlying mechanisms helps you diagnose “netcode” complaints and tune interpolation/prediction parameters for your specific game’s feel.

Take This to Production

Start with the fundamental principle: UDP for state, reliability for events. Send player positions, rotations, and velocities via unreliable UDP datagrams 20-30 times per second. Send critical events (damage, pickups, ability activations) via a custom reliable channel built atop UDP with sequence numbers and ACKs.

Implement client-side prediction for all local player actions. When the player presses a button, execute the action immediately in your local simulation, then reconcile with the server’s authoritative result when it arrives. This single technique makes your game feel responsive even on poor connections.

Run bash setup.sh to explore a working multiplayer game demo comparing UDP and TCP protocols side-by-side. The demo simulates multiple game clients, introduces controlled packet loss, and visualizes the dramatic difference in player experience. Watch TCP players freeze and teleport while UDP players maintain smooth motion. Experiment with different packet loss rates and latency configurations to see how each protocol degrades under stress.

Next steps:

Profile your game’s network traffic, identify your critical vs. non-critical data, and implement a tiered reliability system. Build telemetry to measure player-reported “lag” against actual network metrics—often what players call lag is prediction error or hitbox desync, not network latency. Master these patterns, and you’ll ship games that feel responsive and fair, even for players on challenging connections.